Front Porches, Trail Rides and Stories of Black Futures

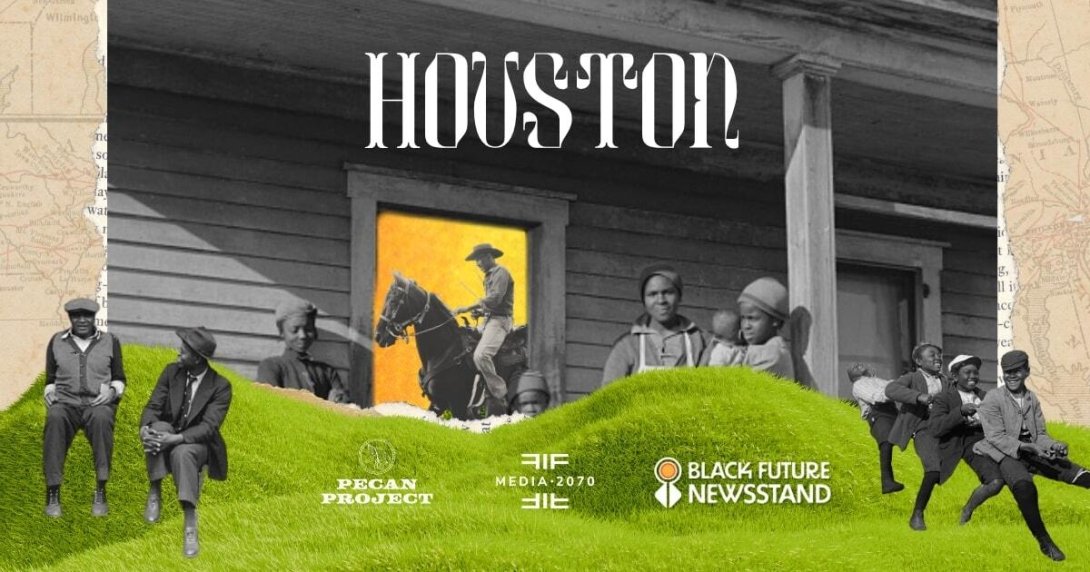

Beginning on Oct. 31, the Media 2070 project will co-host its fifth Black Future Newsstand (BFN) exhibition, with scheduled events running through mid-November.

This latest installment, which is happening in Houston, will once more ask attendees to imagine “what does a media system that loves Black people look and feel like in a future where reparations are real?”

It’s a question that Media 2070 has been asking since its founding in 2020 — and it’s a question we’ve posed to BFN attendees since our very first exhibit in 2023.

For the first BFN, which Media 2070 co-hosted in Harlem with the Black Thought Project, we constructed a sturdy wooden newsstand that we filled with Black publications that depicted a world where media reparations had been realized. Blackboards hung on the newsstand’s outer walls, asking visitors to take a piece of chalk and respond to questions such as “What do you love about yourself?” and “What stories do you long to see about Black people in the media?”

The BFN has since evolved. Last May, a reimagined BFN debuted in Los Angeles. Grandma’s living room — rather than a newsstand — symbolically represented another example of an information infrastructure that serves the well-being of Black communities.

Media 2070 and the Preserving Essential Cultural Archives & Narratives (PECAN) Project are co-hosting Houston’s BFN, where a front porch will serve as the latest example of a critical information ecosystem that exists in many Black communities.

“It’s a place where stories can be told, where in the right circumstances, [people are] safe and have this space to thrive and nurture,” said Diamond Hardiman, Media 2070’s reparative narrative and creative strategy director. It’s also a space, Hardiman noted, where “intergenerational conversation” happens.

”It also allows for “interact[ing] with nature and the world around us,” she added.

Telling the story

The Houston BFN is the most dispersed newsstand event to date. Various locations throughout the city and in deep East Texas will host events over a three-week period.

Media 2070 will showcase a BFN exhibit at the AfroTech Conference in Houston through Oct. 30. The exhibit features the kind of chair found on many porches; it will rest between circular glass portals that connect the past to the future.

Sanman Studios will host BFN’s opening public event on Oct. 31, which will feature live performances, storytelling roundtables and a replica of a front porch. An art gallery, curated by Alexis Pye, will showcase the work of Houston artists who are exploring the commodification of Black Southern culture as well as issues around land and labor rights that Black communities face. Cultural workers will read poems and short stories about reproductive rights and environmental justice.

Various BFN events are happening in November:

- The Reading Room, an “independent reference library for Black art and culture” in Houston, is hosting a teach-in about the visual strategies of Black women artists whose work addresses issues of rematriation, land stewardship and memory.

- The PECAN Project is hosting a trail ride with Big Body Ryders and Ice House Radio in Lufkin, Texas, on Nov. 8. This trail ride will also address reproductive rights and climate justice in deep East Texas. It will run alongside the South Eastern Rodeo Association 12th Annual Rodeo.

- The final event —Neo-Sowl: Third Coast Communion — will occur on Nov. 14. It is “a sacred sonic gathering — a meditation in motion, merging neo-soul frequencies, live instrumentation, and spoken word into a collective sound healing rooted in Third Coast traditions.” For BFN, the gathering will reimagine “neo-soul through Houston’s historically and predominantly Black soundscapes … to the rural heartbeats of East and Central Texas.”

Documenting history

Each BFN has reflected the hopes of realizing a just world where the health and well-being of Black people, Black families and Black communities are respected, protected and just a reality of everyday life.

These hopes should not be an aspiration, or something that has to be struggled for. They should just be.

But our nation has yet to reckon with its history of anti-Black racism. This legacy has infused the social and political structures in our society that have upheld a system of racial hierarchies.

This includes our nation’s news-media and cultural systems, which have played a powerful and destructive role in the production and distribution of anti-Black narratives — which in turn have undermined the realization of a just, multiracial democracy.

The emphasis on the front porch during Houston’s BFN is an effort to visually capture a critical information infrastructure that exists in many Black households and Black communities. But the front porch also evokes how segregation and segregationist policies have shaped powerful meaning-making institutions such as journalism.

“The porch and the living room [are] both like an honor, and it’s a place that I wish existed regardless, but it is a result of exclusion,” said Hardiman. “It is the result of marginalization because we don’t have these larger institutions to rely on when it comes to documenting and archiving our own stories and histories in general.”

She added that large media companies are also “certainly not getting the story right ever in the first place.”

Houston’s BFN will feature several journalists, artists and cultural organizers who are archiving and documenting these histories and stories that connect the past, present and future. They are creating the kind of information infrastructures that need support — infrastructures that are serving the health and well-being of Black people and Black communities.

These include the work of Houston native Uyiosa Elegon and deep East Texas native DaLyah Jones.

Shift Press

Uyiosa Elegon is one of the featured speakers at Houston’s BFN — and the co-founder of Shift Press, a youth publication that is featured in this year’s newsstand.

A few years shy of 30, Elegon has already dedicated a considerable amount of his life to working on youth issues, which he considers critical “to the survival of the Earth.”

“It really does go that far for me,” he said.

In high school, Elegon was a member of the Houston Independent School District Student Congress. During his tenure, he worked with the Houston Independent School District on amending a student code of conduct to make it “more equitable and comprehensible for students.” He also authored a section of an amicus curiae brief that called on the Texas Supreme Court “to declare the Texas school finance system unconstitutionally inadequate.”

In 2017, Elegon and five other Student Congress members created the Institute of Engagement, a youth collective whose mission was to “help young people take responsible ownership of their Houston.”

During the time Elegon spent organizing students and other young people, he witnessed the harmful role that local-media outlets have played when covering the city’s youth population.

“My peers, and myself, had really poor experiences with the journalism landscape in Houston as [youth] organizers,” said Elegon.

He recounted that the Houston Chronicle watered down a column a fellow student wrote. He experienced the media’s refusal to cover the activism against the governor’s anti-Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions legislation. And he had “terrible conversations” with journalists when he was organizing a coalition of elders in a historically Black neighborhood.

Now, years later, Elegon believes local-news coverage has only gotten worse. He called the local-TV newscasts of ABC13 and KHOU “cop media” — noting that these stations criminalize the city’s Black and Brown communities as well as pro-Palestinian organizers.

Despite these experiences, Elegon was still a fan of journalism and journalists like David Fahrenthold, a Houston native, who now works for The New York Times, and Emily Ramshaw, the former editor-in-chief of The Texas Tribune, who is the co-founder and CEO of the 19th.

In 2020, Elegon and two members of the Institute of Engagement founded Shift Press, a youth publication. As the outlet’s website notes, it’s “hard for young people to get news that’s relevant to their lives.”

The site also states that Shift Press “provides news and journalism training that encourages Houston youth civic engagement” and believes “more youth-produced media and better informed youth” will result in “a healthier, better educated, and more prosperous” city.

Since its founding, Shift Press has provided journalism training for about 200 young people. Elegon estimates that 90 percent of the people who received training came from activist backgrounds.

During the week of Oct. 27, the site is featuring articles youth journalists have written on topics ranging from mental health and advocacy to state legislation that would ban bathroom access for trans people.

Meanwhile, the publication now has nine editors, seven of whom are paid contractors and two of whom are volunteers. It pays each contributing youth journalist $300 per article. The three Shift Press staffers — including Elegon — are paid $25,000 per year.

Currently, Elegon works part time at the publication. He works full time as the senior community outreach organizer for Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit advocacy organization.

One of the challenges facing Shift Press is the lack of funding opportunities in Texas for youth news organizations.

The PECAN Project

DaLyah Jones is the founder and editorial director of the PECAN Project, a cultural-memory and reparative-journalism initiative that is “dedicated to preserving the legacy of Black placemaking in East Texas.”

Jones is an Afro-Texan from deep East Texas, a region that borders Louisiana and is shaped by the history of colonization, the slave trade and white supremacy.

Following the Civil War, the formerly enslaved established Freedom Colonies in Texas that were heavily concentrated in East Texas. As The Texas Freedom Colonies Project notes: They were “intentional communities created largely in response to political and economic repression by mainstream white society.”

Texas has the largest Black population of any state in the country.

During the 20th century, the oil, lumber and railroad industries became dominant forces in the region. Industrialization impacted the lives of Black people and Black landowners in deep East Texas and throughout the South.

In 2024, Jones wrote that Black landowners in the South “lost 12 million acres of farmland over the past century,” noting that “most of this loss occurred in the 1950s due to discriminatory lending practices, violence or intimidation, and tax sales.”

Jones has written about the history of white-supremacist violence in deep East Texas: the dangers of “sundown towns,” the public lynchings, mob violence, the brutal murder of James Byrd in 1998 in Jasper. This history has impacted how Jones views herself and her community. She came to understand this impact even more when she moved away.

“If somebody is reflecting to you an inaccurate story about who you are and your value in the world, you’re gonna internalize that and then you’re going to move from that place,” said Jones, who did just that when she moved away for college. She later worked as a journalist for Austin’s NPR station and then for The Texas Observer.

“It took me literally moving and going to college for me to realize a lot of the injustices that were happening at home,” said Jones. “I’m a firm believer that you don’t know what you don’t know until you know.”

Jones’ personal and professional experiences have reinforced her belief that reparations are also about “spiritual reclamation.”

The PECAN Project’s focus on environmental and reproductive justice is an effort to redress the harms the lumber and oil industries have inflicted on the land and its people.

Jones notes that the lumber and oil industries in deep East Texas have “eviscerated one of the most … ecologically diverse forests in the world and in the nation.” This concerns her when it comes to addressing the struggle for environmental and reproductive justice.

“What does that mean to the ways in which we relate to ourselves? If we think that we’re separate from the land, then what does that say about our relationships to ourselves?” Jones said.

Relating to each other is essential to the struggle for reparations and repair, which are about “spiritual reclamation.” This is embodied in the trail ride the PECAN Project has organized for BFN.

“A trail ride was historically to drive cattle from one place to another,” Jones said, “[but] … after a while it literally became a heritage or a cultural event. Black … people would come together after a cattle drive to celebrate and party together.”

When we’re talking about celebration, she added, “these are … modes of resistance, modes of resilience as well.”

Learn more about Black Future Newsstand: Houston and donate to support Media 2070’s programming.