Trump's Corrupt Plan to Steal Rural America's Broadband Future

Drastic changes the Trump administration is making to a broadband program will unjustly enrich Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos.

Flickr user Gage Skidmore

The old saying “timing is everything” apparently also applies to corruption.

On June 6, mere hours after Elon Musk started his tweet war with the president, Trump’s Commerce Department released its long-awaited revisions to the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (“BEAD”) program.

This $42 billion broadband-deployment plan was part of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (“IIJA”) that Congress passed in November 2021. As expected, the Trump administration’s revisions radically overhauled what had been a rural broadband-deployment plan focused on building fiber networks — and turned it into a free money dispenser for Elon Musk’s satellite-broadband company, Starlink.

Had this billionaire bromance fallen apart a few weeks earlier, we might have seen a less sweeping revision of this once-in-a-lifetime infrastructure program. But now that this revised plan is out there, analysts everywhere — operating on the premise that Trump-administration corruption is a given — are trying to predict how and to what degree the Trump team will enforce these changes designed to unjustly enrich Musk … a man the president reportedly called “a big time drug addict” as the two traded barbs.

The failures of the first Trump FCC’s broadband plan

The BEAD program is a rare example in this polarized era of Congress managing to pass legislation designed to improve people’s lives. BEAD was supposed to be a long-overdue and long-lasting solution to the lack of broadband deployment in some rural areas. It promised funding and priority status for future-proof and robust fiber-broadband networks, if states chose to go that route, empowered as they were to make these decisions thanks to the language in the law Congress passed. The IIJA did not require states to choose the cheapest possible solutions to a longstanding infrastructure problem, or to skew money toward subsidies for satellite-broadband providers, all to reward them for satellites they’d already launched and service they were already providing.

Though it seems like ages ago, there was genuine bipartisan enthusiasm about BEAD upon its passage in late 2021. The pandemic focused Congress’ attention on America’s infrastructure gaps, making it abundantly clear that the government’s prior efforts to address the rural digital divide were at best piecemeal. Congress acted in the wake of then-FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s bungled $9.2 billion “reverse auction” rural deployment program. That late 2020 effort — known as the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (“RDOF”) — initially sent the largest subsidy awards to tiny firms with no established track record. It also had nearly a billion dollars in free money provisionally awarded to Musk’s Starlink, all to provide a less-robust satellite-broadband service — and one that was already deployed — to many places where no one lives or works (like highway medians) or that were already well served (like major international airports).

Fortunately, the Biden FCC stepped in and canceled the most wasteful of these provisional RDOF awards, like the one that would have paid Musk to “deploy” Starlink service to the Pentagon’s parking lot. The Biden FCC’s actions ensured that these funds, which were raised via a regressive tax, would be used to subsidize deployment only in places where people actually live. But even a reformed RDOF program had failures and shortcomings that left millions of rural homes and businesses without a robust, affordable broadband option.

Congress’ bipartisan “priority broadband” subsidy plan

Shortly after President Biden took office, Congress got to work on an infrastructure bill. The pandemic’s devastating impacts motivated this work. At a time when people needed affordable and reliable broadband to log into work, remote schooling and telehealth appointments, Congress could no longer ignore — or play political games over — the economic and social consequences of the lack of truly universal deployment. It is important to keep in mind that lawmakers began their work months after Starlink’s commercial launch grabbed headlines.

The House version of the bill (H.R. 3684), delivered to the Senate on July 1, 2021, did not contain any broadband subsidies. This early version of the IIJA received only two Republican votes, and the Senate’s 60-vote filibuster rule left a lot for legislators to hammer out. In addition to then-Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and then-Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, a “gang” of 21 senators worked to reach an agreement on the bill, with the Republicans holding considerable leverage because of the need for at least 10 GOP votes to reach the 60-vote threshold.

After a month of negotiations, the bipartisan negotiators in the Senate emerged with a dramatically overhauled IIJA, which included the $42.5 billion BEAD program, and the $14.2 billion Affordable Connectivity Program (“ACP”). After another 10 days of amendments and debate, the Senate adopted its version of the IIJA. The final vote on passage in the Senate, on Aug. 10, 2021, was 69–30. All of the “no” votes came from Senate Republicans, but 19 Republicans did vote “yes” — including those who were part of the bipartisan negotiating gang and several more.

Current Senate Majority Leader John Thune was not part of this group, but during the 117th Congress that passed the bill, he was the ranking member on the Senate Commerce subcommittee that has jurisdiction over broadband. Notably, even though Thune had strong views and input on the final bill, he voted no. His explanation for this no vote had nothing to do with the amount of money allocated to BEAD, or how it prioritized future-proof broadband technologies like fiber, or even how it left oversight of each state’s implementation of the program to the executive branch and not the FCC (a provision he did object to). Instead, Thune justified his no vote for the entire bill by saying that the IIJA was not “fully paid for.”

Focusing on what Thune said prior to and after IIJA’s adoption provides important insight into congressional intent, especially now that the GOP-led Senate has undermined its own authority to please an authoritarian president and his wealthy benefactors. While the plain language of the IIJA makes it clear that Congress did not intend for BEAD to fund the lowest-cost technology, that’s exactly what the Trump administration is now requiring. While it would be inefficient and wasteful to require fiber deployment to every nook of the entire country, that’s not what the IIJA required, it’s not what the Biden administration required the states to do and it’s not what the states were planning to do before the Trump administration froze their work.

Congress’ not-so-neutral infrastructure mandate

Let’s take a look at the language of the IIJA, focusing specifically on how Congress instructed the states and the executive branch — via the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) within the Commerce Department — to prioritize the spending of BEAD’s $42.5 billion.

The IIJA instructs states to “prioritize funding for deployment of broadband infrastructure for priority broadband projects,” and to allocate funding first to unserved locations, and then to underserved locations. The law defined an unserved location as one that “has no access to broadband service; or lacks access to reliable broadband service offered with a speed of not less than 25 megabits per second for downloads; and 3 megabits per second for uploads; and a latency sufficient to support real-time, interactive applications.”

The IIJA required states to rely on the FCC’s “fabric” broadband-mapping data to make these determinations, data that Congress required the FCC to collect in a separate law, and which would not become available until November 2022. Nevertheless, at the time satellite-broadband service was available to 100 percent of the United States, meaning there were actually zero locations that had “no access to broadband service.” So the most important task for the FCC, NTIA and states was determining which areas lacked “25/3” megabits per second (“Mbps”) low-latency broadband. And while the IIJA didn’t define a latency threshold, the FCC had used 100 milliseconds (“ms”) since 2013. This meant in practice that locations with access only to geostationary satellite-internet services (like Viasat) still would qualify under the IIJA as “unserved.”

But what about low earth orbit (“LEO”) satellite services like Starlink? Starlink started selling service to the public in 2020, to much fanfare, so Congress clearly was aware of it. During its first months of operation, Starlink was not yet available across the entire country, with some users put on a waitlist. However, where it was immediately available, it purportedly did meet the 25/3 Mbps and 100 ms latency thresholds.

This raises a really important question. Why did Congress appropriate $42.5 billion for a broadband-deployment program when it knew that Starlink, Amazon and other LEO broadband providers had already deployed — or were in the process of deploying — service to the entire country?

The answer is obvious. Congress wanted to fund something more robust than satellite- or mobile-broadband services. “Technological neutrality” is a buzzword that politicians and lobbyists like to throw around, but the IIJA didn’t instruct states to be indifferent; Congress put its thumb heavily on the scale of future-proof technology, a status that not all broadband technologies can claim.

Congress funded easily scalable networks, not those that turn to dust every five years

We can see this in the IIJA’s definition of a “priority broadband project” and in IIJA’s instructions on what factors to prioritize. The section of the IIJA outlining BEAD’s “order of awards” tells states to prioritize unserved areas ahead of underserved, and notes that “priority broadband projects” should receive priority.

What does that priority status mean? The law directs states to “give priority to projects based on deployment of a broadband network to persistent poverty counties or high-poverty areas; the speeds of the proposed broadband service; the expediency with which a project can be completed; and a demonstrated record of and plans to be in compliance with Federal labor and employment laws.”

That section is relatively clear, both in terms of what is mentioned and what is not. Poor areas go before rich areas. Faster networks go before slower networks. When deciding between proposed networks of similar speeds, the project that can be completed faster gets extra weight. And companies with a record of labor-law compliance are favored over those with either no track record or a poor one. Nowhere in the BEAD statute did Congress direct the NTIA or the states to prioritize minimizing a project’s construction costs.

In fact, Congress’ definition of a “priority broadband project” is yet another clear indication of its intent for states to fund as much fiber deployment as possible. A “priority broadband project” is one that is “designed to provide broadband service that meets speed, latency, reliability, consistency in quality of service, and related criteria as [the NTIA] shall determine. And it is one that “ensure[s] that the network built by the project can easily scale speeds over time to meet the evolving connectivity needs of households and businesses; and support the deployment of 5G, successor wireless technologies, and other advanced services” (emphases added).

It would be hard to argue that satellite networks “can easily scale speeds over time,” especially compared to fiber-optic networks. The former require the massive expense and technical logistics of continually launching new satellites into space, while the latter require minor changes to local network equipment, if even that. While LEO satellites have a shelf life of about five years (due to deorbiting from atmospheric drag), fiber-optic networks can last as much as 50 years, according to AT&T.

But most telling is the clause about supporting “the deployment of 5G” and successor wireless technologies. Today’s wireless networks absolutely need fiber, essentially at every tower or node. Where no fiber is available, 5G networks can use other terrestrial point-to-point wireless backhaul transmissions to get as quickly as possible to a fiber node. LEO’s role in the cellular industry is confined to a back-up signal option when there’s no cellular service available. In other words, LEO isn’t capable of “supporting” 5G networks, merely complementing them.

If this “support 5G” networks clause seems oddly specific to you, that’s because it is. It reflects a top priority of Thune’s, one he expressed at the time the Senate was crafting the BEAD program.

On July 2, 2021 — the day after the House delivered its version of IIJA to the Senate — Thune published an Op-Ed extolling the virtues of 5G. In the piece, he noted that “broadband networks” are a “significant part of the 5G technology equation.” The South Dakota senator referenced Senate testimony from the CEO of a fiber-optic broadband provider in his state — noting that Congress should be “listening to the advice of these experts” to “properly support the deployment of reliable and resilient networks without wasting taxpayer dollars.” In his testimony from the prior week, this South Dakota telecom CEO stated “how critical a fiber foundation is to every kind of communications technology — wired or wireless. Fiber not only offers the most efficient and economical means of meeting consumer demand well into the future, but it also is essential to our nation’s 5G future.”

While the Trump NTIA is now pretending that project cost is the only factor to consider — and that satellite technology is what Congress had in mind when it created the BEAD program — this is revisionist history. Elon Musk himself has made it clear that Starlink was always intended as a last-ditch solution. Speaking at a satellite conference in 2020, Musk stated “Starlink will effectively serve the three or four percent [of the] hardest to reach customers for telcos, or people who simply have no connectivity right now.” Even the first Trump FCC’s bungled RDOF plan placed less-capable LEO satellite services like Starlink in a tier below gigabit-capable services, despite then-Chairman Pai’s assertion that the RDOF was also “technology-neutral.”

The Biden NTIA’s common-sense interpretation of the law

As soon as then-President Biden signed the IIJA, the NTIA started developing guidance for state-funding agencies. In May 2022, NTIA released this guidance in the form of the BEAD Notice of Funding Opportunity (“NOFO”), and did so seven months ahead of the FCC releasing the first “fabric” broadband map the IIJA required. This comprehensive document dealt with all of the tasks Congress had delegated to the NTIA, not only defining terms like “priority broadband project” but also the myriad of other things the IIJA required (including recommendations on the low-cost broadband option, resiliency reporting and other things that anti-Biden critics bemoan).

The Biden NTIA defined a “Priority Broadband Project” as one “that will provision service via end-to-end fiber-optic facilities to each end-user premises,” subject to an “Extremely High Cost Per Location Threshold.” NTIA adopted this Priority Broadband Project definition after determining that this end-to-end fiber requirement was the best fit for Congress’ requirement that grants for priority projects should be used for technologies that “ensure that the network built by the project can easily scale speeds over time to meet the evolving connectivity needs of households and businesses; and support the deployment of 5G, successor wireless technologies, and other advanced services.”

NTIA explained how fiber meets this congressional requirement, noting that “end-to-end fiber networks can be updated by replacing equipment attached to the ends of the fiber-optic facilities, allowing for quick and relatively inexpensive network scaling as compared to other technologies. Moreover, new fiber deployments will facilitate the deployment and growth of 5G and other advanced wireless services, which rely extensively on fiber for essential backhaul.”

NTIA also offered states guidance on how to decide among competing Priority Broadband Project applications, directing states to give weight to those that “minimize” total BEAD outlay, as well as projects that are more affordable to end users. The NTIA also directed states to prioritize applicants with a strong track record of fair labor practices (or new entrants who made such commitments). Other factors included providers’ speed to deployment, offers of open access, and coordination with local or tribal governments and stakeholders.

NTIA’s determination that only end-to-end fiber projects met the IIJA’s definition for “Priority Broadband” faced some congressional pushback. However, it was not because NTIA generally excluded LEO satellite from that category. It was because the agency determined that fixed wireless projects that exclusively rely on unlicensed spectrum also could not be considered “reliable broadband” (another term the IIJA required NTIA to fully define).

Therefore, if a location was served only by such a provider, that location would be considered “unserved” and eligible for BEAD. Thirteen Republican senators wrote the NTIA that “fiber, fixed wireless, and cable providers have all demonstrated an ability to reliably serve customers at the 100/20 mbps required speed, an ability to scale up service over time, and an ability to support deployment of other advanced telecommunication services.” Nowhere in this letter did these senators mention LEO satellite.

Lessons from the three states that received final NTIA approval

Contrary to the Trump administration’s rhetoric, the Biden NTIA’s progress on BEAD was remarkably fast, especially considering that this process involves 50 U.S. states and five territories administering their own programs. The Biden NTIA had approved the initial proposals for all states and territories, and most states were in the middle of their final challenge processes (during which ISPs could challenge a location’s inclusion or exclusion).

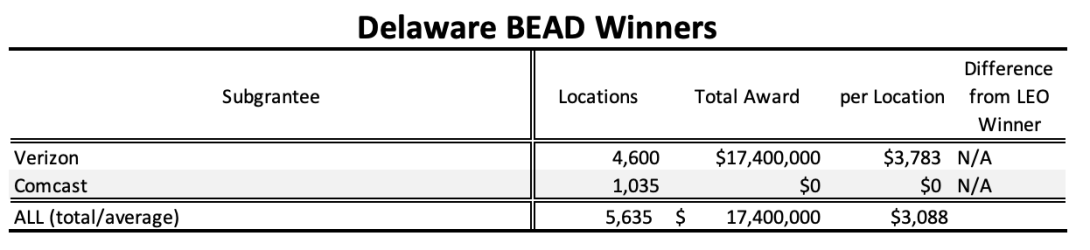

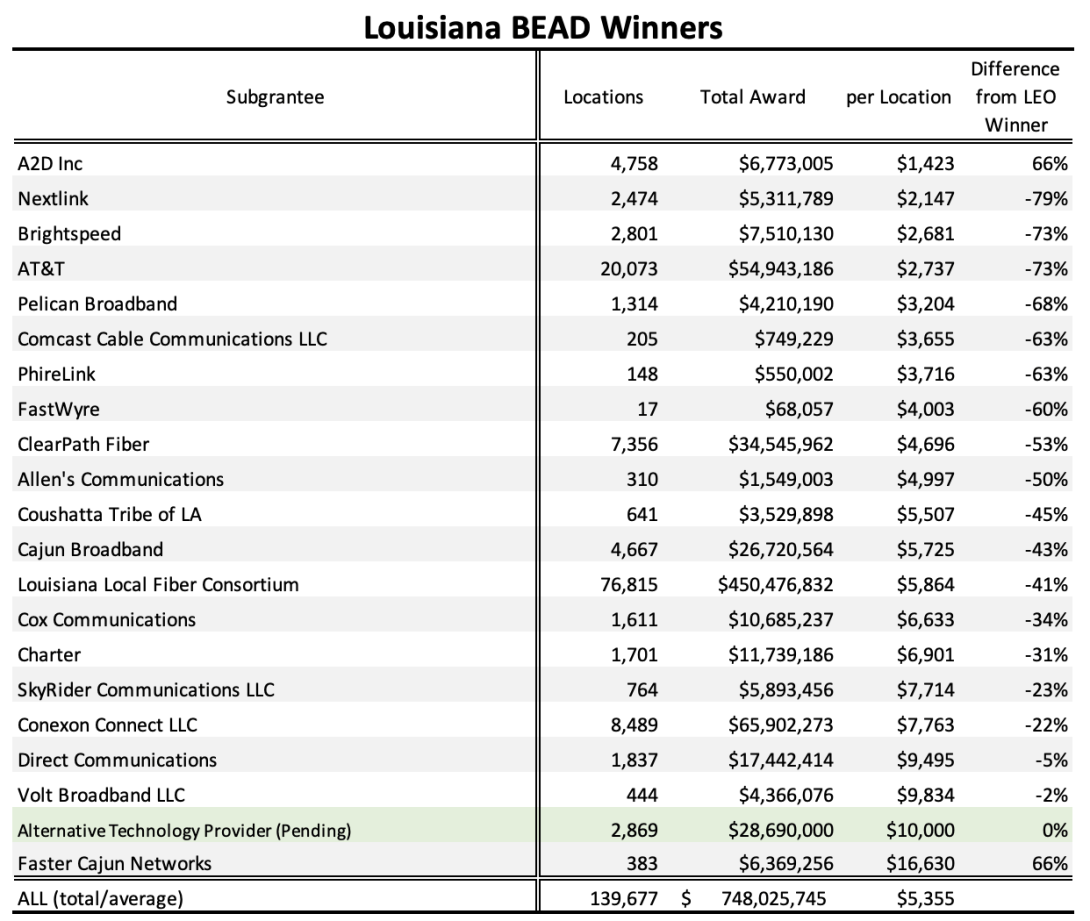

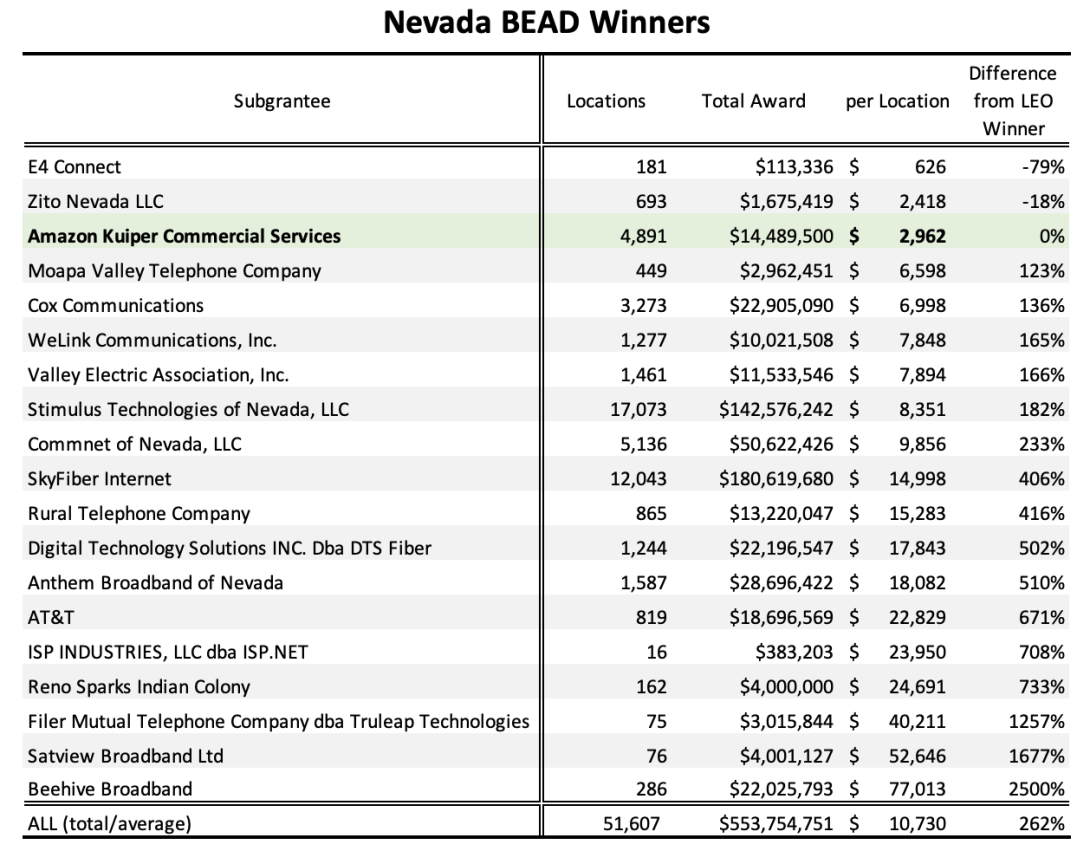

Three states (Delaware, Louisiana and Nevada) had received their final approvals and announced their winning awards before the Trump administration froze the BEAD program. We can take a look at these three geographically different states’ results to see how they allocated their awards and how they determined their Extremely High Cost Per Location Thresholds.

In keeping with Congress’ decision in the IIJA to empower states to decide how to best administer their BEAD awards, the Biden NTIA did not set a specific dollar amount for the Extremely High Cost Per Location Threshold. Most states decided to determine this value after going through the initial round of bids. Because of that, we have this information only for the three states that received final NTIA approval.

Delaware did not set a high-cost threshold at all, as it was able to cover 100 percent of its unserved and underserved locations with money left over. (Though the state’s Department of Technology and Information did note that it would have set that threshold at $100,000 if it had had to.) Interestingly, Comcast claimed nearly 20 percent of eligible locations in Delaware with a $0 bid, committing $22.3 million of its own money to bring fiber-optic services to these locations (at approximately $22,000 per location).

Louisiana set its Extremely High Cost Per Location Threshold at $100,000. After conducting two bidding rounds and one round of direct negotiation, Louisiana had 43 locations with bids exceeding that cost threshold. The state assigned those 43 locations above the $100,000 threshold “to lower-cost Reliable Broadband Service or Alternative Technology applications,” (e.g., fixed wireless, or cable modem). In its final proposal, Louisiana noted that “2,869 locations received no application interest at all from Priority or Reliable technology types during either of the two primary rounds or the Direct Negotiation process, and as a result have been selected for an Alternative Technology.”

Louisiana set aside $10,000 per location for these Alternative Technology (i.e., LEO satellite, fixed wireless or hybrid-fiber coaxial) projects. It is unclear, though, why Louisiana chose this amount, as it’s questionable for the states to direct any subsidy awards to LEO ISPs other than for the user’s equipment and installation costs (which are far less than $10,000 per location; Starlink currently charges $349 for its residential equipment, which users install themselves).

Nevada is the second-most urban U.S. state (with 94 percent of its population living in urban areas), but its rural locations are extremely isolated. That may explain why Nevada set its Extremely High Cost Per Location Threshold at $200,000, double that of Louisiana and Delaware. As Nevada conducted its bidding rounds, locations that only received Priority Broadband Project bids exceeding this threshold were later redirected to “Alternative Technologies” like LEO satellite or fixed wireless, as the NTIA required. Together these Alternative Technologies accounted for about 20 percent of all BEAD-eligible locations in Nevada, with Amazon’s forthcoming LEO satellite company Kuiper Commercial Services selected to cover about half of these at a cost of just under $3,000 per location.

When comparing Louisiana’s and Nevada’s winning bids, the differences in per-location costs is stark. Louisiana was able to entice fiber bids to 98 percent of its eligible locations for under $10,000 per location, averaging a subsidy cost of about $4,700 per location. In contrast, Nevada covered 80 percent of its eligible locations with fiber, at an average per-location cost of approximately $12,000, a figure that is heavily weighted by the several hundred locations that exceeded $50,000 per location.

Is $70,000 — excluding the ISP’s contribution — too much to spend to bring fiber to a single location? Most people might think so, especially when Starlink’s LEO satellite service is available to all of those locations right now. But this is the freedom and flexibility that Congress gave states when it created BEAD as an infrastructure program usable for sorely needed, high-capacity networks. Congress was well aware of Starlink, Amazon Kuiper and other LEO ISPs, yet still chose to allocate that much money to subsidize infrastructure that can “easily scale speeds over time to meet the evolving connectivity needs of households and businesses; and support the deployment of 5G, successor wireless technologies, and other advanced services.”

Corruption trumps common sense

On June 6, after wasting nearly five months to “fix” what it deemed a “woke” program — a sentiment Thune cynically echoed — Trump’s NTIA finally released its “revised” Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO). While the revisions go well beyond the central issue of NTIA’s interpretation of “Priority Broadband Project,” we’ll focus for now on those particular changes, as they are the most consequential — and also the most corrupt.

The Trump NTIA’s changes were essentially what most analysts expected on this score: a change in the definition of “Priority Broadband Project” that will unjustly enrich Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos and their LEO satellite companies, which will be the only broadband option for millions of rural families. The Trump NTIA now defines “Priority Broadband Project” as “a project that provides broadband service at speeds of no less than 100 megabits per second for downloads and 20 megabits per second for uploads, has a latency less than or equal to 100 milliseconds, and can easily scale speeds over time to meet the evolving connectivity needs of households and businesses and support the deployment of 5G, successor wireless technologies, and other advanced services.”

Yes, that’s right. Trump’s NTIA simply changed the definition to the one Congress already adopted for underserved areas, and melded that together with the latter half of the statutory provisions on priority networks’ need for scaling, evolving and supporting advanced service. In doing so, NTIA failed to follow the law, which directs the agency to “determine” the criteria that states need to use when deciding if a particular technology can “provide broadband service that meets speed, latency, reliability, [and] consistency in quality of service.” At best, the Trump NTIA defined the speed-and-latency minimums, but did nothing to interrogate what is necessary for a service to be considered reliable or consistent in quality of service.

Resorting to this circular definition — which merely parrots the meaningful and yet very general terms in the statute itself — would not alone put inordinate amounts of BEAD funding into the already overstuffed pockets of Musk and Bezos. The Trump NTIA also directed states to follow a single primary criterion: They now “must select the combination of project proposals with the lowest overall cost to the Program.”

Nowhere in the revised NOFO does the Trump NTIA consider what would make a service “reliable” or able to deliver “consistency in quality of service.” Nowhere in the revised NOFO does the Trump NTIA even consider how states should determine if a proposed project can “easily scale speeds over time to meet the evolving connectivity needs of households and businesses and support the deployment of 5G,” leaving states little if any room to push back on an applicant’s self-certification and promises in this regard.

Under the Trump NTIA’s revisions, the only flexibility left to states when considering competing applications arises if the competing bids are within “15% of the lowest-cost proposal received for that same general project area on a per [location] basis.” If that is the case, then and only then can states consider the “speed to deployment,” the “speed of the network and other technical capabilities.” States also can give extra weight to proposals they’d approved before the Trump NTIA stepped in to overhaul the NOFO.

Given the results for Nevada, where Amazon’s LEO service put in the second-lowest per-location bid of $3,000, it’s very likely that these Trump NTIA revisions will pay for very little fiber deployment — that is, unless the NTIA decides not to enforce its revised NOFO. Why would it do that? Well, for one, Musk and Trump are no longer (publicly) tied to each other, and Trump may reverse course yet again and direct his NTIA not to do Musk any favors. But more likely is that the Trump administration uses these revisions selectively, and uses BEAD to reward red states and governors Trump favors, while punishing blue states.

This is a hugely disruptive and destructive change that undoes months of meticulous work every single state has done. That rug-pulling, along with the fact that the new NTIA tossed out a complete definition of “Priority Broadband Project” and replaced it with an incomplete one, raises the specter of lawsuits. However, the problem for the states and ISPs — which thought they were about to break ground on broadband-construction projects — is that the IIJA limits judicial review.

Under the law’s judicial-review standard, litigants must show that the NTIA assistant secretary’s “decision was procured by corruption, fraud, or undue means; [that] there was actual partiality or corruption in the Assistant Secretary; or the Assistant Secretary was guilty of misconduct in refusing to review the administrative record; or any other misbehavior by which the rights of any party have been prejudiced.” The Trump administration’s lawlessness is self-evident from its poor track record in court in 2025, but the IIJA sets a pretty high bar for any potential litigant.

With all this said, the states may still have one way to prevent most of their BEAD awards going into Musk’s bank account: Starlink has a poor track record at meeting the NTIA (and FCC’s) minimum speed requirements. Ookla, the company behind speedtest.net, just released a study that found “only 17.4% of U.S. Starlink Speedtest users nationwide were able to get broadband speeds … of 100 Mbps download [ ]and 20 Mbps upload.” Ookla noted that while Starlink had shown improvements since the last report in 2022, its median download speed in the United States during the first three months of 2025 was 104.71 Mbps and its median upload speed was 14.84 Mbps.

These are median values, meaning half of Starlink’s first-quarter Ookla tests are below these thresholds and already fail to meet the Trump NTIA’s watered-down standard. Indeed, diving into Ookla’s market-specific data turns up numerous locations where Starlink doesn’t come close to meeting the downstream thresholds, much less the upstream. For example, in Gulf Shores, Alabama, Ookla’s March 2025 data show an average Starlink downstream speed of 87 Mbps and upstream speed of 13 Mbps. In Lehigh Acres, Florida, Ookla’s March 2025 data show an average Starlink downstream speed of 82 Mbps and upstream speed of 12 Mbps.

However, even if states try to use these subpar performance results to push back against the NTIA’s satellite preference, they may still be stuck with Musk and Bezos. And that’s because of the method that NTIA requires states to use to contract with LEO satellite companies. As the Biden NTIA noted, “with LEO service, [ ] there is no defined network dedicated to fixed locations in which the Federal government could take an interest to ensure performance.”

In other words, with terrestrial projects, states would award grants for physical infrastructure to be built to specific locations, while satellite-broadband networks use satellites that are already orbiting the earth (or which could be launched into orbit). Because of this difference, there’s not much incentive for satellite companies to actually sign up customers in the BEAD award areas. Indeed, LEO ISPs are incentivized to allocate their limited bandwidth to the highest-paying customers regardless of location, and that’s business-class customers.

To address this perverse incentive, the Trump NTIA proposed a somewhat convoluted “bond” scheme, in which the LEO ISP “reserves” capacity for every eligible location in the areas for which it wins BEAD grants, regardless of whether every potential customer signs up. Under this system, the states would release only a portion of the subsidy award up front (50 percent is the example cited), holding the rest of the award back as a bond. The grantee would then receive the additional funding depending on how many customers it signs up in its award areas (e.g., the bond “can be reduced by an additional 25% of the original amount after the subscription rate reaches at least 25% of all locations in the project area”). But because the states would be contracting for a specific capacity, the LEO providers could simply assert they will meet that obligation by deprioritizing customers in unsubsidized areas.

The consequences of corruption

If this all seems pretty far afield from how lawmakers in both parties originally characterized BEAD — as a lasting solution to the digital divide that represented a “generational investment” — it’s because the Trump administration’s changes were not made with the public interest in mind. The Trump administration also can’t pretend that it’s making fiscally responsible changes. That’s because while the subsidy cost to deploy may be reduced on paper, there is no legitimate reason at all to subsidize LEO satellite-broadband deployment.

Starlink’s and Amazon Kuiper’s entire business model is to make money selling satellite services where wired-broadband services are not available, and likely never will be. And Starlink is literally available right now to every single one of the more than 7 million unserved and underserved locations in the United States. Giving BEAD money to Musk to do something he’s already done is the height of foolishness, waste, fraud and abuse.

If the Trump NTIA’s actions wind up sending tens of billions of taxpayer dollars to Musk and Bezos to subsidize investments that they were already planning to make, it would be another log on the dumpster fire this incompetent and corrupt administration stokes daily. But free money isn’t all that’s driving Musk and Bezos. Starlink’s and Project Kuiper’s long-term interest is in monopolizing rural markets, so they have captive customers who have no regulatory recourse if these satellite services fail to deliver as promised, or raise prices to unreasonable levels.

If Congress wanted Musk’s Starlink to be the solution for rural areas, it wouldn’t have written the law telling states to spend the money on future-proof, easily scalable technology, nor given states the power to determine how and where to spend on that infrastructure. But as is the theme with the Trump administration, what the law says does not matter half as much as what Trump and his minions want.

Thanks to Donald Trump, millions of people who would have otherwise gotten robust fiber-optic internet service will get nothing more than what they have right now: slow broadband, no broadband or Musk’s expensive satellite service. This is no accident. Trump bragged about this to Joe Rogan’s audience in October 2024, with the presidential candidate hawking Starlink long before he turned the White House’s South Lawn into a Tesla used-car lot. But the president’s whims, feuds and personal enrichment schemes are no better a reason to make broadband policy than they are for any of the other corrupt, unconstitutional and dangerous maneuvers this administration has made.

Help Free Press keep fighting for affordable and reliable internet access: Donate today.