Reclaiming MLK's Legacy

As our nation celebrates the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. today, it’s critical — now more than ever — to reclaim his legacy.

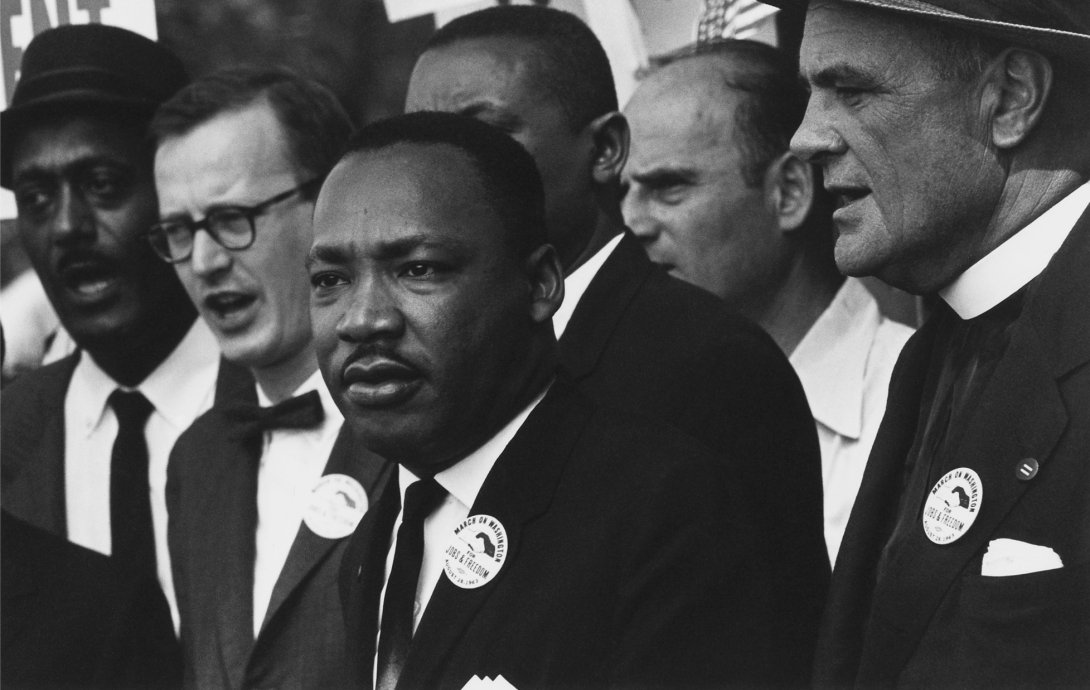

For years, politicians and the press have played a major role in sanitizing King by tethering his legacy to his “I Have a Dream” speech at 1963’s March on Washington.

As journalist and author Gary Younge has written, the speech is “hailed not as a dramatic moment of mass, multiracial dissidence, but as a jamboree in Benetton Technicolor, exemplifying the nation’s unrelenting progress toward its founding ideals.”

Sanitizing King’s legacy is a deliberate act. It erases what King fought for — economic equality, and opposition to the Vietnam War — in the years following his speech.

It also obscures the U.S. government’s campaign to destroy King afterward.

Campaign targeting MLK

The Church Committee’s 1976 report on the government’s illegal domestic spying activities found the FBI had feared King’s March on Washington speech — which it called “‘demagogic’” — because it established him as the “‘most dangerous and effective Negro leader in the country.’”

The FBI sought to “‘take him off his pedestal’” and “select a candidate to ‘assume the role of the leadership of the Negro people.’”

In addition, the Church Committee found that the FBI used “every intelligence-gathering technique at the Bureau’s disposal” to collect information about the private activities of King and his advisors and “‘completely discredit’” them.

In 1964, before King accepted the Nobel Peace Prize, the FBI sent him a tape-recording of his extramarital affairs that it had gathered by bugging his hotel rooms. In a note it sent with the recording, the FBI urged King to commit suicide or be exposed.

And the Church Committee report stated that by 1968, the FBI feared King could become a potential “‘Messiah’” and unify the “‘Black nationalist movement’” by abandoning his “‘White liberal doctrines’” of non-violence.

“In short,” the Church report noted, “a non-violent man was to be secretly attacked and destroyed as insurance against abandoning non-violence.”

Sanitizing King also avoids any conversation about how unpopular he was within the white community for his campaigns that challenged institutional and structural racism following the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

King addressed this issue head on in his final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?:

“With Selma and the Voting Rights Act one phase of development in the civil rights revolution came to an end. A new phase opened, but few observers realized it or were prepared for its implications. For the vast majority of white Americans, the past decade — the first phase — had been a struggle to treat the Negro with a degree of decency, not of equality.

“White America was ready to demand that the Negro should be spared the lash of brutality and coarse degradation, but it had never been truly committed to helping him out of poverty, exploitation or all forms of discrimination.

“The outraged white citizen had been sincere when he snatched the whips from the Southern sheriffs and forbade them more cruelties. But when this was to a degree accomplished, the emotions that had momentarily inflamed him melted away. White Americans left the Negro on the ground and in devastating numbers walked off with the aggressor. It appeared that the white segregationist and the ordinary white citizen had more in common with one another than either had with the Negro.

“When Negroes looked for a second phase, the realization of equality, they found that many of their white allies had quietly disappeared. The Negroes of America had taken the President, the press and the pulpit at their word when they spoke in broad terms of freedom and justice. But the absence of brutality and unregenerate evil is not the presence of justice. To stay murder is not the same thing as to ordain brotherhood.

“The word was broken, and the free-running expectations of the Negro crashed into the stone walls of white resistance. The result was havoc. Negroes felt cheated, especially in the North, while many whites felt that the Negroes had gained so much it was virtually imprudent and greedy to ask for more so soon.”

Resurgent White nationalism

Nearly 50 years after King’s assassination, fully embracing his legacy still threatens the preservation of a White racial hierarchy.

But that’s all the more reason why we must challenge any efforts to sanitize or otherwise undermine the struggle for racial justice — especially given the current political climate.

Our nation just elected a president who ran a racist campaign from day one. And from that first day the broadcast and cable networks aired uncritical coverage of Donald Trump spewing racist rhetoric that reached millions of households.

Trump was ratings gold. And as CBS President Les Moonves said last year about the Trump campaign: “Who would have thought that this circus would come to town? But, you know, it may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.”

Moonves might as well have just said that racism is good for business.

And now in the election’s aftermath, many in the mainstream media have expressed regret over their failure to pay more attention to those White voters who chose to elect a president who embraced — and was embraced by — White nationalists.

Major media outlets have expressed little (if any) regret, however, about placing profits over the physical well-being of communities of color, who Trump targeted on the air and on other popular media platforms.

That’s why reclaiming King’s legacy today is really about saying out loud that the institutional and structural racism that he — and so many others — fought to dismantle still remain deeply embedded in our nation’s social and political life.

And the fight for racial justice won’t stop no matter how deliberately those in power try to prevent that from happening.